Of course the ceasefire deal is the main topic currently in the news, but the abrupt resignation of ICJ President Nawaf Salam to become Prime Minister of Lebanon shouldn’t be overlooked. It’s another example of the many things wrong with the system of international law we have in place today.

The United Nations General Assembly and Security Council are political institutions which countries use to pursue their foreign policy interests. For that reason the UN Charter also established the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to offer opinions based solely on international law rather than politics. This is what the ICJ was charged to do in its decision last July regarding Israel’s occupation.

In order for the ICJ to remain nonpolitical it is composed of a panel of 15 judges, each a citizen of a different nation. These judges are sworn not to represent their home country’s government, or even to be influenced by it. Instead, they are to be guided solely by their conscience and their understanding of the law.

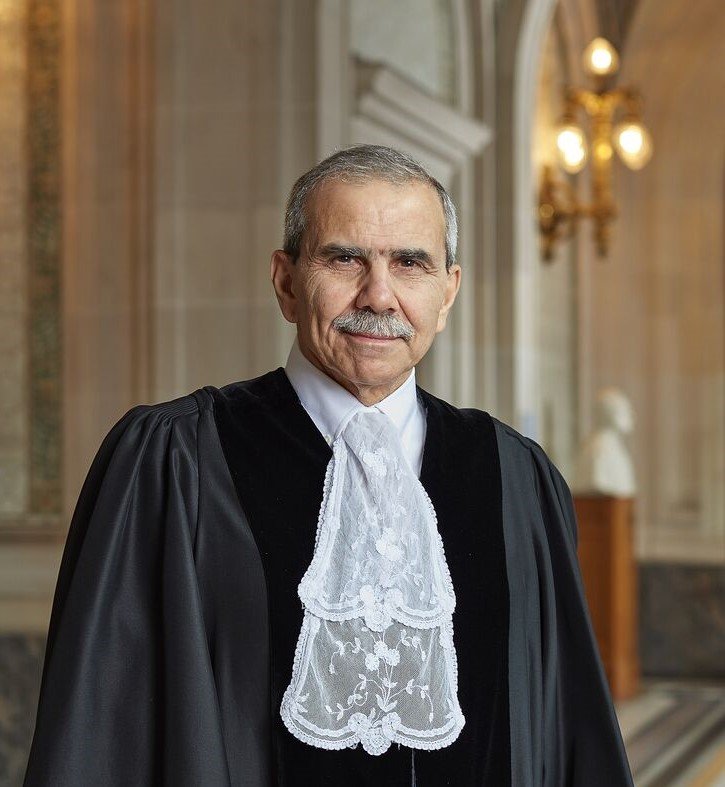

During the period in which hearings about the legal status of Israel’s occupation were held and the advisory opinion was written, Judge Nawaf Salam of Lebanon served as president of the ICJ. In addition to having served as Lebanon’s representative to the UN, he also has an impeccable legal resume.

The ICJ opinion was harshly critical of Israel. It declared Israel’s continued presence in the occupied territories illegal, said that Israel must withdraw from all the territories, including East Jerusalem, as rapidly as possible without regard for Israel’s historical ties to those places and regardless of the extent to which such a withdrawal endangers Israel’s security, and that Israel must uproot all of its citizens that currently reside in the areas in question. Court President Salam added his own separate declaration, in which he expressed anti-Israel views even stronger than the court’s majority and found Israel guilty of Apartheid.

While it’s tempting to accuse the court of anti-semitism and anti-Israel bias, we must think long and hard before questioning the motives of those with whom we disagree. The opinion weighs difficult legal issues that people may see differently. The fact that the court’s president was from Lebanon, a known enemy of Israel, is also not an indication that the ICJ is biased as an institution. The fifteen judges come from all around the world and there wouldn’t seem to be anything untoward about the Lebanese judge being chosen as chief.

But on January 13th ICJ President Salam abruptly resigned his position to become Lebanon’s new Prime Minister. One day he was an international judge sworn not to be influenced whatsoever by the political positions of his home country, then the next day he was in charge of formulating and advancing the same political positions he had been sworn to ignore.

At this point one has to wonder to what extent the court’s opinion, and certainly Salam’s personal declaration, were not unbiased legal interpretations but rather were written with an eye towards currying favor in Lebanon.

It would be best for the ICJ to have a code of ethics mandating a ‘cooling off period’ of at least a year or two during which a former judge cannot be appointed to or campaign for a political office. That way there would be less incentive for judges to use their ICJ opinion writing to audition for jobs back in their home countries and less reason for those reading court decisions to suspect that is going on. But the ICJ doesn’t currently have such a rule, and so Salam was able to make this overnight transition. That’s a shame, because for an international court to have any standing to deliver a legal opinion on a political controversy it needs to be seen as one hundred per cent impartial and entirely above politics.

Salam concluded his separate declaration by stating that he has participated in the present proceedings with the deep conviction that he is using law and justice to lay “the foundations for a just and enduring solution to a conflict that has lasted far too long.” But is the ICJ opinion truly a solution based on law and justice, or is it a list of politically motivated demands designed primarily to resonate with the Lebanese public that he phrased in the language of law?

Salam’s abrupt transition gives us every reason to wonder. Israel and its supporters have yet another valid reason to believe that the international legal system has been rigged against it by politics. On top of that, the job of anyone who wants to promote reliance on impartial international justice is now even harder.